Occasionally, I let slip that I spent a decent chunk of my life living in Wales. As I teach archery, this commonly leads to the question of whether it’s legally sound to shoot a Welshman with a longbow in Chester or Herefordshire or whichever town or county the questioner can think of that borders Wales or Scotland. Occasionally, extra parameters are added: “It’s fine as long as you’re near the cathedral at midnight and you shoot exactly 12 yards”. That sort of thing.

This idea is so prevalent that even the people that run the country—or at least want to run the country—sometimes get confused. But is it actually legal?

The short answer is, somewhat obviously: no, it isn’t legal. Historic royal decrees and the wobbly process of defining a British person as legally Welsh, English or Scottish aside, murder is still murder, even when it’s perpetuated on the Welsh.

The longer answer is that it was never really a fully fledged law to begin with, and that even if it had been it’s been totally superseded. There are a few theories about how this urban myth came about, but the most likely theory seems to be somewhat ironically based around a decree written by the Prince of Wales. The Prince of Wales in 1403, that is; not the current incumbent.

It is a matter of historical record that the English and Welsh (and Scottish) have not always seen eye to eye. Despite Welsh archers being common in English armies (including during the famous so-called English victory against the French at Agincourt), loyalties to the Crown were largely dependent on what year it was and who nominally governed any given piece of land.

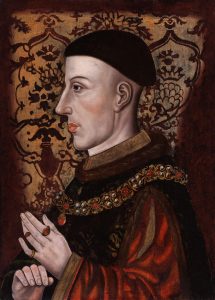

In the early fifteenth century, Prince Henry of Monmouth, Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, was concerned about Welsh uprisings in and around Chester. Sir Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy had defected to join forces with Owain Glyndŵr, who was busy causing trouble for the English throughout Wales. Percy and Glyndŵr were unhappy with the then-King Henry IV, who had usurped the throne from Richard II.

During the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, Percy was killed by an arrow to the face. Prince Henry was nearly done for in the same way, but he was saved and left with a permanent scar. Worried about the possibility of further defection to the Welsh cause, Prince Henry (who later became King Henry V) decreed that there should be a curfew on Welshmen in Chester:

“…all manner of Welsh persons or Welsh sympathies should be expelled from the city; that no Welshman should enter the city before sunrise or tarry in it after sunset, under pain of decapitation.”

Welshmen were required to leave their weapons at the town gates and not congregate in groups of three or more. And shooting a Welshman in Chester? Archery was never specifically mentioned in the Prince’s request, at least not that anyone seems to be able to reliably report.

A few years later in 1408, the citizens of Chester elected a Welsh mayor, John Ewloe. There were periodic troubles between Ewloe’s allies and the constable of the castle, William Venables, but these came to an end in 1411 when Venables was forced to pay reparations to certain citizens of the city. In short, Chester itself didn’t have a bone to pick with the Welsh.

In summary: don’t shoot a Welshman with an arrow, even if the person asking you to do so was born in Monmouth and is the reigning Prince of Wales.